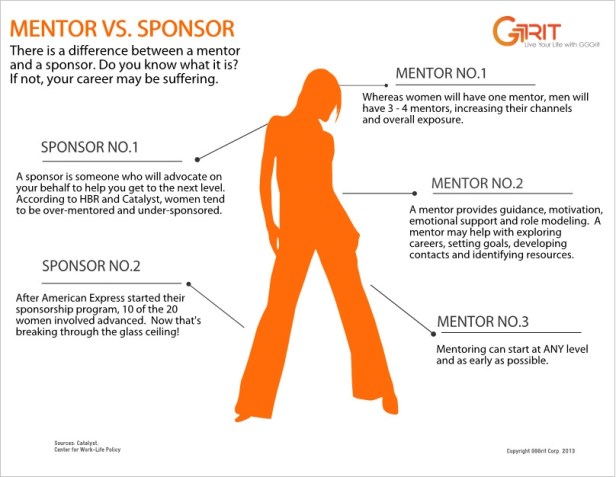

Ao contrário de um mentor, que oferece aconselhamento e permite que seu pupilo desabafe sobre questões como o equilíbrio entre a vida no trabalho e a vida pessoal, um padrinho (“sponsor”) geralmente é alguém que está dois degraus acima na hierarquia corporativa e que defende a promoção de uma determinada pessoa.

As cartas dirigidas à Timóteo, Tito e Filemon fazem parte de um subgrupo importante dentre as cartas do apóstolo Paulo. Elas não são direcionadas às igrejas de uma cidade ou região. Elas são cartas para apóstolos. Estes líderes fariam parte da segunda geração de líderes e Paulo estava investindo tempo e recursos para seu desenvolvimento. Eles deveriam enfrentar o crescimento das heresias e da perseguição do Império Romano. Muitos apóstolos de segunda geração cruzariam a Europa, Ásia e África para manter as igrejas estabelecidas pelos apóstolos. Eles enfrentariam oposição contínua dos bispos das grandes igrejas de Roma e Antioquia, ansiosos por manter uma estabilidade com os governos locais. Essa decisão iria facilitar o projeto de poder de Constantino e frear o avanço do Cristianismo para outras reinos e Civilizações. Se você quer saber se possui características de um apóstolo, leia as cartas à Timóteo, Tito e Filemon. Se deseja ser um pastor local, leia as demais cartas do Novo Testamento. Ao longo do tempo você se tornará um mentor, e então, um patrocinador de pessoas.

Sylvia Ann Hewlett, autora do livro “Forget a Mentor, Find a Sponsor” diz que essa relação é uma troca transacional. “Para atrair um padrinho, você precisa ser um talento. A pessoa mais graduada precisa acreditar em você e também que você contribuirá para o sucesso dela”. Ela diz que esta é uma maneira efetiva de designar uma coisa da qual os homens sempre se beneficiaram historicamente: o clientelismo e as redes de cumplicidade.

Sylvia diz que o mentor, que aconselha os jovens, não é suficiente. As mulheres têm de achar um profissional graduado e influente que possa selecionar, no mar de gente da média gerência, as profissionais realmente talentosas (não as mais identificadas com características de “macho”, e sim as mais eficientes). Toda boa empresa tem pelo menos um profissional assim. O caminho é identificá-los – e convertê-los.

Sylvia diz que o mentor, que aconselha os jovens, não é suficiente. As mulheres têm de achar um profissional graduado e influente que possa selecionar, no mar de gente da média gerência, as profissionais realmente talentosas (não as mais identificadas com características de “macho”, e sim as mais eficientes). Toda boa empresa tem pelo menos um profissional assim. O caminho é identificá-los – e convertê-los.

Na opinião de Sylvia, que comanda o Center for Talent Innovation, um centro de estudos sobre diversidade e gerenciamento de talentos dos Estados Unidos, as mulheres são muito boas em fazer amizades no trabalho, mas têm muita dificuldade em usufruir delas. Já os homens não têm esse problema, pois dão um valor diferente às relações no trabalho. “A única coisa que importa é o poder. As mulheres, instintivamente, escolhem a pessoa errada. Elas tendem a escolher um líder que querem copiar, um modelo. Em vez disso, deveriam escolher alguém que tenha poder”, diz.

Além disso, elas tendem a subestimar o significado de ser apoiada por alguém da cúpula. “As mulheres pensam que o que deveria importar é o desempenho. Elas querem uma meritocracia pura”, diz Sylvia. Danica Dilligard, sócia da consultoria e auditoria Ernst & Young (EY), diz que as mulheres tendem a ser excessivamente tuteladas e pouco apadrinhadas. “Elas recebem muitos conselhos, mas não têm um suporte claro”, enfatiza.

Kerrie Paraino, vice-presidente sênior internacional de recursos humanos da companhia de cartões de crédito American Express, observa que os padrinhos têm muito mais a perder – e potencialmente a ganhar – que os mentores. “O primeiro acaba usando sua influência e capital político para ajudar você a progredir na carreira. Já o segundo não arrisca sua reputação com um pupilo”, ressalta.

Um padrinho, portanto, também deve sair ganhando da relação. Fiona Hathorn, da Women on Boards UK, afirma que ele pode se beneficiar por ter ajudado pessoas de diferentes regiões e departamentos a desenvolverem suas carreiras. Randall Peterson, professor de comportamento organizacional da London Business School, diz que é melhor quando esse suporte não vem do supervisor direto, pois ele pode ter interesse em manter você na equipe e inibir sua promoção.

______________________________________________________________________________

Companies increasingly realize that winning in the global marketplace requires a workforce that “matches the market” — yet talented women, people of color, and gays too often stall before they reach the top. What can help them break free of the “marzipan layer,” that talent-rich tranche just below senior management? The answer is sponsorship — a strategic workplace partnership between those with power and those with potential.

The biblical letters to Timothy, Titus and Philemon are part of an important subgroup among the letters of the apostle Paul . They are not directed to the churches of a city or region . They are letters to the apostles . These leaders were part of the second generation of leaders and Paul was investing time and resources to their development . They should face the growth of heresy and persecution of the Roman Empire . Many second-generation apostles would cross Europe , Asia and Africa to keep the churches established by the apostles . They face continual opposition of the bishops of the great churches of Rome and Antioch , eager to maintain stability with local governments . This decision will facilitate the design of power of Constantine and stop the spread of Christianity to other kingdoms and civilizations. If you think that have characteristics of an apostle, please read the letters to Timothy, Titus and Philemon . If you want to be a local pastor , read the remaining letters of the New Testament . Over time you will become a mentor, and then a sponsor of people.

As I explain in my book “Forget a Mentor, Find a Sponsor: The New Way to Fast-Track Your Career,” sponsorship differs from the better-known concept of mentorship in important ways. A mentor is a counselor who will lend a sympathetic ear, act as a sounding board, and offer advice and encouragement. Mentors can help you understand the unwritten rules, provide a map for the uncharted corridors to power, and reveal “the business behind the business” — and research from the Center for Talent Innovation shows that the vast majority of women (85 percent) and multicultural professionals (81 percent) need navigational help.

Sponsors, on the other hand, are people in positions of power who work on their protégé’s behalf to clear obstacles, foster connections, assign higher-profile work to ease the move up the ranks, and provide air-cover and support in case of stumbles. Mentors advise; sponsors act.

With sponsorship, the ambitious and highly qualified make it to the senior-most suite, no matter how stiff the headwinds. Without it, they languish in the lower echelons — no matter how hard they work, no matter how well they perform.

Sponsorship translates into quantifiable career traction. When it comes to asking for a pay raise, the majority of women (70 percent) resist confronting their boss; with a sponsor in their corner, 38 percent of women summon the courage to negotiate. Women with sponsors are 22 percent more likely to request getting assigned to a high-visibility team or plum project. And fully 68 percent of sponsored women feel they are progressing through the ranks at a satisfactory pace, compared to 57 percent of their unsponsored peers. That translates into a “sponsor effect” of 19 percent for women. CTI research shows that sponsors affect women’s career trajectory even more profoundly than men’s in at least one respect: 85 percent of mothers employed full-time who have sponsors stay in the game, compared to only 58 percent of those going it alone. That’s a sponsor effect of 27 percent.

The sponsor effect on professionals of color is even more striking. Minority employees are 65 percent more likely than their unsponsored cohorts to be satisfied with their rate of advancement.

It’s not easy to find a sponsor. For starters, sponsorship must be earned — by delivering outstanding performance, die-hard loyalty, and a distinct personal brand (something the sponsor prizes but may intrinsically lack, such as gender smarts, cultural fluency, or the unique perspective resulting from being a woman, gay or a person of color on a team that’s mostly white males).

Women and minorities have an additional challenge to attracting sponsors: the “mini-me syndrome.” Senior leaders naturally prefer to sponsor people they feel most comfortable with — members of “their tribe,” who speak the same language, follow the same customs and look like them. With white men making up the vast majority of senior leaders, it’s not surprising that the people they choose to sponsor are other white men.

Formal sponsorship programs can help bridge that gap. The Center for Talent Innovation has helped seed 17 sponsorship programs at major corporations, with tangible results for both sponsors and protégés. For example, nearly one-third of the protégés at Bristol-Myers Squibb have been promoted, as have one-third of the sponsors. Thirty percent of the 60 protégés in Intel’s “Extend Our Reach” sponsorship program have taken on expanded jobs, and nine were promoted to vice president.

At American Express, where women make up 60 percent of its global workforce but only 18 percent of its executive managers, the company has put eight groups of 15 to 20 women through a formal program. More than one-third have since been promoted or given broader responsibility. “The exposure the women were given through their sponsors facilitated moves that perhaps would not have happened otherwise,” said Valerie Grillo, the chief diversity officer for American Express.

CTI research demonstrates a robust correlation between diversity and market growth. Innovative capacity resides in an inherently diverse workforce where leaders prize difference, value every voice and manage rather than suppress disruption — in other words, where sponsorship enables women, multicultural professionals and gays to reach their full potential.

That bottom-line imperative is why international law firm Crowell & Moring partnered with CTI’s advisory arm on an initiative to promote sponsorship. In an article in the Washington Post, chair Kent Gardiner explains:

“The firm’s future rests on this sponsorship initiative. If you enhance the diversity and perspectives and ways of thinking about a problem based on different life experiences, different approaches, you create more opportunity for innovation. You’re not trying to solve the problem the same way you did the last 10 times.

“So we’ve got to get this right.”

Republicou isso em Blog Paracletoe comentado:

Um mentor espiritual é aquela pessoa já está na estrada e que ajuda outra pessoa a caminhar. O mentor ajuda o outro a experimentar e se relacionar com Deus. E mais – a viver as conseqüências dessa relação com Ele – o Pai. É um papel auxilar a ser feito com humildade de servo e ter o Espirito Santo como companheiro essencial. É o próprio Deus que deseja esse relacionamento.

O mentor não deve dar uma de quem já sabe o caminho ou para garantir êxito ou, o que é pior, tentar impressionar o mentoreado. Também não pode agir como se nada tivesse a oferecer, pois como diz Paulo:

“Portanto , todas as pessoas, devem nos considerar servos de Cristo encarregados dos mistérios de Deus” I Co 4

O mentor deve esperar e observar que o mentoreado tenha um maior e crescente apego e descobrir a vontade de Deus para sua vida sendo capaz de acolher também o ensino bíblicoda igreja e não só sua própria voz interior. O mentor deve ter uma base sólida de doutrina ( Evangelhos – principalmente o de João, cartas de Paulo aos Romanos e aos Efésios) para orientar o mentoreado pois um comportamento seriamente incompatível com o ensino bíblico e os desejos de Deus só trará perturbações a um relacionamento com o Pai. Paulo ensinou aos Gálatas:

“Irmãos, se alguém for surpreendido em algum pecado, vós que sois espirituais, deveis restaurar essa pessoa com espírito de humildade. Todavia, cuida de ti mesmo, para que não sejas igualmente tentado.” Gálatas 6

No marketing multinivel, seu mentor imediato, teoricamente, deve ser seu patrocinador – ou o líder mais competente de sua upline imediatamente acima de você. Ele deve lhe dar as coordenadas do negócio, do trabalho a ser feito, da postura a ser adotada e, inclusive, deve munir-lhe com informações, treinamentos, cursos e conselhos de outros mentores. Mentores esses que provavelmente já o ajudaram. Essa é a palavra mágica do multinível: “duplicação”. Isso significa que seu mentor/patrocinador deve “duplicar” tudo o que ele já aprendeu e que já pôs em prática. E esse é o grande objetivo desse post: ajudá-lo a evitar tentar inventar tudo por conta própria.